Software Capitalization Rules under FASB and GASB

The capitalization of software development costs was a consideration for accountants as early as 1985. Over 35 years ago the FASB issued Statement No. 86 Accounting for the Costs of Computer Software to Be Sold, Leased, or Otherwise Marketed to provide specific guidance where none previously existed. Accounting guidance for computer software, in general, was published, but nothing specifically addressed internally-developed software for sale.

The accounting profession has progressed rapidly since the 1980s, as has business and commerce. Several additional rules have either been published or amended as our use of software has become more prevalent and the types of software arrangements offered have expanded. Most recently ASC 350 Intangibles – Goodwill and Others (ASC 350) was originally published in early 2015, effective beginning in 2016.

However, stakeholders requested further clarification during the comment period and after, applying the updated rules throughout 2016. The FASB published Subtopic ASC 350-40 Customer’s Accounting for Implementation Costs Incurred in a Cloud Computing Arrangement That Is a Service Contact (ASC 350-40) as an amendment to ASC 350 in 2018 specifically for internal-use software. The updates to ASC 350-40 were effective for public entities for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 2019.

The history of software capitalization for state and local governments is similar to that of FASB. Issued June 2007, GASB Statement No. 51, Accounting and Financial Reporting for Intangible Assets (GASB 51) provides a summary of rules regarding software capitalization to provide consistency for how organizations account for intangible assets. However, the evolution of technology and increased use of software required additional standards and clarification. In 2020, therefore, GASB issued Statement No. 96, Subscription-based IT Arrangements (SBITAs) (GASB 96) effective for fiscal years beginning after June 15, 2022, to address contracts for software services. While the FASB’s software capitalization rules target the development cost or the cost to obtain software, GASB is focused more on the implementation costs related to SBITAs.

Types of software

As introduced above, accounting for software has evolved as offerings have increased. When reviewing the accounting treatment of software, three main categories should be considered:

- Purchased software

- Internally-developed software

- Software as a service (SaaS)

Purchased software

Software first appeared to the consumer and smaller businesses as an asset to purchase. It was developed and sold by very few companies, such as HP and IBM, who had experience with computer technology and were the first pioneers of the technological revolution.

In the very early days, software applications were purchased on a floppy disk or diskette. The disk itself had no significant value, but the information or coded instructions on the disk could be an intangible asset. While software is rarely ever sold as a disk, a company will occasionally purchase “out-of-the-box” or “off-the-shelf” software. This terminology is applied when no customizations or enhancements are needed for the software to be used by the purchaser.

As technology has evolved, the format by which software is purchased has also evolved to a download of information or coded instructions from the internet versus a tangible disk.

Purchased software under FASB

When software is purchased by an entity and used without any customizations or configuration, under FASB accounting standards it is recorded on the balance sheet as an intangible asset at the purchase price and amortized over its economic or legal life, whichever is shorter. The economic life is the period over which the intangible asset contributes to the cash flows of an organization. The legal life is the contractual term of the intangible asset. If the asset has an indefinite useful life, it is not amortized but must be analyzed periodically for impairment of value.

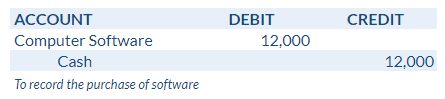

Here is an example of a journal entry for the purchase of software for $12,000 applying FASB guidelines.

Purchased software under GASB

GASB 51 explicitly names computer software as an intangible asset owned by state and local governments. Under this guidance, the software is treated as a capital asset recorded on the statement of financial position at its purchase price and amortized by a rational and systematic method over its useful life, or if its usefulness is determined to be indefinite, it would not be amortized.

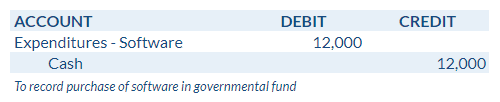

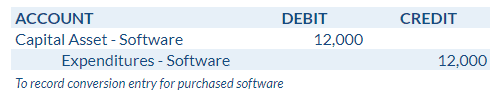

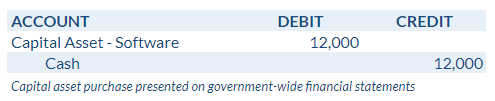

However, when software is purchased by a governmental fund, the purchase is recorded as an expenditure because capital assets are not current financial resources. Later, when creating government-wide financial statements, a conversion entry is recorded to reclass the expenditure to a capital asset. The combined entries leave software as a capital asset purchased for cash on the consolidated government-wide financial statements, shown below.

Internally-developed software

As organizations became more familiar with and increasingly relied on technology, more customization occurred. To gain an advantage over competitors, entities now wanted software developed for their particular needs. Either an organization purchased software off the shelf to enhance itself, contracted with the vendor to customize, or the organization developed software internally. In each case, additional guidance was published to provide for the capitalization of some of the development costs. Furthermore, as more companies entered the technology industry, standards were also drafted to establish guidance for software developed internally to be sold.

Internally-developed software under FASB

Under the FASB guidance, software capitalization rules for software purchased or developed with internal use in mind vary from the rules regarding software for sale.

Internal use

In general, the implementation costs, or costs after planning and design, for internal-use software are capitalizable while the ongoing maintenance costs are not. To explain further, costs related to:

- purchases of software or software licenses,

- software development,

- coding and testing, or

- purchases of external materials

are the types of expenses to capitalize. Any costs related to the ongoing operation of software or software licenses such as training, manual data conversion, or maintenance and support costs are not capitalizable.

For sale

When software is developed for sale or external use, the accounting treatment differs slightly. The capitalizable and non-capitalizable costs are still determined by where or when in the development process they occur, but the guidance becomes more granular. Costs to develop external-use software are not capitalizable until the software is declared technologically feasible

Technological feasibility is determined after planning, designing, coding, and testing. If these preliminary steps lead to a realistic product, the remaining development work for features and functionality – from both internal resources and third parties – can be capitalizable.

Internally-developed software under GASB

The GASB’s accounting treatment for software has different criteria than the FASB’s.

Internal use

Software for internal use is an intangible asset and is considered to be in scope under GASB 51. GASB 51 allows for costs related to the application development stage of software creation to be capitalized. The application development stage is defined as the stage after the product has been declared technologically feasible but before maintenance and ongoing operation. Installation, testing, and parallel processing are deemed to be application development activities, but training is defined as a post-implementation activity.

For sale

External-use software, or software developed to sell, is excluded from the scope of GASB 51 and should follow the guidance for investments, GASB 72, Fair Value Measurement and Application (GASB 72), as an asset held by the government primarily for profit. Investments under GASB 72 are generally measured at fair value.

Software as a Service (SaaS)

More recent changes to software and its use resulted in a movement towards cloud computing arrangements and software subscriptions. These arrangements may be referred to as SaaS along with other types of services such as platform as a service (PaaS) and infrastructure as a service (IaaS) as well. PaaS is a cloud-hosted platform for developing, maintaining, and managing applications whereas IaaS is cloud-hosted physical and virtual servers functioning as the infrastructure for running applications and workloads in the cloud.

With these types of service arrangements, an organization is not purchasing a specific software, but instead, a license or subscription to use the software over a specific period of time. Additionally, as technology has evolved, the licenses or subscriptions have moved to be available over the internet or in the cloud.

SaaS under FASB

The answer to this evolution for FASB was the issuance of ASC 350-40 in 2018. Under ASC 350-40 certain implementation costs for cloud computing or hosting arrangements can be capitalized. Read our article ASC 350-40: Internal-Use Software Accounting & Capitalization for more details on this accounting update.

Organizations now have numerous software applications spread over most, if not all of their various departments. To have better visibility into software costs and usage, organizations should consider developing a SaaS spend management strategy.

Managing multiple software applications can result in overspending, lack of control, and inaccurate financials. SaaS spend management platforms provide a central administrative place to manage, optimize, and govern software purchased and used by employees. The first step is to track all SaaS products with LeaseQuery’s SaaS contract tracker.

SaaS under GASB

GASB also issued new guidance to address accounting for IT services. GASB 96 was published in 2020 and became effective for organizations with fiscal years beginning after June 15, 2022. The standard was written to mirror GASB 87 in that once an organization determines they have a SBITA within the scope of GASB 96, they establish a subscription asset and subscription liability based on the total expected payments to be made over the subscription term.

We have published an article summarizing the accounting concepts of GASB 96 that includes a comprehensive example of applying GASB 96 for further explanation of the accounting treatment proscribed in the statement.

While GASB organizations are required to establish a subscription asset and subscription liability for SBITAs within scope, FASB does not have a specific requirement at this time. It’s important to manage all software with a SaaS spend platform for the visibility it provides and to be prepared for any additional requirements in the future.

Summary

As with leases, the accounting boards are updating the accounting treatment for software contracts to provide more transparency and consistency to financial reporting. Unlike lease accounting where one completely new standard was issued after forty years, several updates to accounting for technology have been made over the past decades as entities’ adoption of various software has evolved.

As the digital transformation takes us from the simple accounting for a tangible disk to software development costs to various cloud-based service arrangements, the FASB and GASB have issued new guidance to keep up with the progress being made.