Most people grasp the fundamental concept of a successful business: see a need, fill it, and “spend money to make money.” This action of spending is professionally known as the cost of doing business and other expenses. Without tracking this “spend,” you’re just throwing money into a void, hoping for the best—which is not a solid business strategy, unless you’ve accidentally discovered a gold mine in your backyard (in which case, call me).

This is where the Matching Principle swoops in, cape flowing dramatically, to ensure financial reports are grounded in reality.

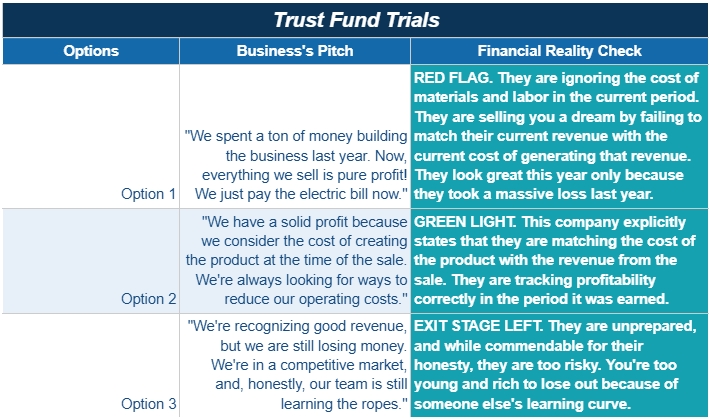

Trust fund trials: Picking a profitable business

Imagine you’ve inherited a huge trust fund. Now, you need to invest in a business that will make your parents and your bank account proud. You’ve been presented with three potential investment opportunities. Which one passes the financial sniff test?

Based on a solid financial perspective, Option 2 is the clear winner because they are following the foundational rule that leads us to this principle.

Based on a solid financial perspective, Option 2 is the clear winner because they are following the foundational rule that leads us to this principle.

What is the matching principle?

The Matching Principle is a core concept under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). It is the engine that drives accrual accounting and is arguably the most critical concept for achieving accurate financial reporting.

Simply put, the principle dictates that a company must recognize the cost of doing business (expense) in the same accounting period as it recognizes the benefit (revenue) of that business.

Cause and effect in financial reporting

Think of it as a financial cause-and-effect relationship:

- The Cause (The thing): Incurring an expense (e.g., buying the materials to make the thing, paying the worker to build the thing).

- The Effect (The benefit): Generating revenue (e.g., selling the finished thing to a very patient customer).

The Matching Principle ensures the financial “cause” and “effect” are reported in the same income statement period. Without it, a company could look artificially profitable one month (recording revenue, delaying the expense) and then unnecessarily unprofitable the next (recording a huge old expense against little new revenue). It’s the difference between looking like a financial genius and a business fraud.

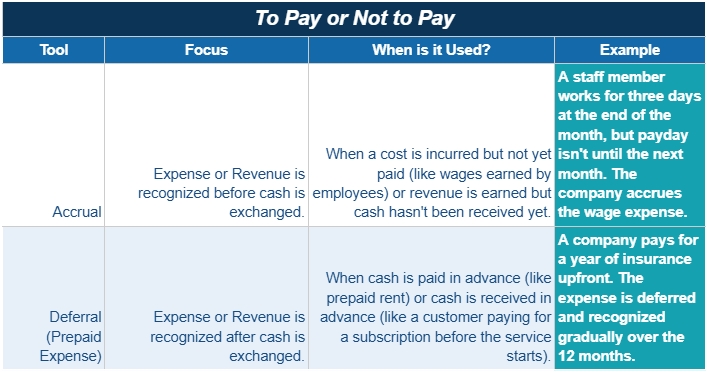

The accountant’s tools: Accruals and deferrals

The biggest challenge with the Matching Principle is the timing—cash doesn’t always move at the same time the revenue is earned or the expense is incurred. This is why accountants employ two primary tools to make sure everything lines up perfectly:

Both tools require adjusting entries at the end of an accounting period (month or year end) to ensure all economic activity is correctly matched.

Both tools require adjusting entries at the end of an accounting period (month or year end) to ensure all economic activity is correctly matched.

Example: Prepaid insurance (a deferral in action)

The classic example of a Deferral is a prepaid expense like insurance:

- December 1st: A company pays $12,000 cash for an annual insurance policy covering the entire next year. Since the company hasn’t used the benefit yet, the full $12,000 is recorded as an Asset (Prepaid Insurance), not an expense.

- January 31st: One month of the insurance is used up. To match the $1,000 cost ($12,000/12 months) to the period of its use, the accountant must recognize it as an expense:

- Adjusting Entry: Debit Insurance Expense $1,000; Credit Prepaid Insurance $1,000.

This monthly adjustment ensures that only the insurance cost related to January is shown on January’s income statement, perfectly matching the expense with the benefit received.

Matching across the business

The Matching Principle applies to virtually every expense, ensuring financial statements are honest and reliable.

- Purchase of Inventory (The Direct Match)

- The Concept: When a company buys inventory, it’s an Asset. Only when that inventory is sold does its cost move to the Income Statement as an Expense.

- The Match: The cost of the inventory is matched to the revenue generated from the sale of that specific item.

- Depreciation (The Systematic Match)

- The Concept: Instead of recording the full cost of a $100,000 machine as an expense in the year it’s purchased, the cost is spread systematically over its 10-year useful life.

- The Match: The cost of the asset is matched to the 10 years of revenue it helps to generate.

- Accrued Wages and Salaries (The Accrual Match)

- The Concept: Employees earn their wage every day, creating an expense. If the month ends before payday, the company must record the liability for the work already done.

- The Match: The labor cost is matched to the period the labor was performed, which is when the corresponding revenue was generated.

Why the matching principle matters to you

For any organization that adheres to GAAP, the Matching Principle is non-negotiable.

- Accurate Profitability: By correctly matching all expenses and revenues, the net income truly represents the profitability of the company’s operations for that specific period. No hiding costs or pretending profits are higher than they are.

- Reliable Financial Position: The Balance Sheet accurately reflects the company’s true obligations (liabilities, like accrued wages) and resources (assets, like prepaid insurance).

- Consistency and Comparability: When all companies follow the same rules, investors and analysts can compare the financial performance of different firms, knowing the numbers aren’t based on creative accounting.

In summary, the Matching Principle is the critical link between when cash moves and when economic activity actually happens. It forces accountants to ask the crucial questions: “When did we actually incur this cost?” and “When did we actually earn this revenue?” The answer drives the timing of journal entries, ensuring the integrity and reliability of all financial reporting.